Day sixteen

The day before, on Sunday, we went to Pisa and returned to Florence not too late. We had a chance to rest on the commuter train, so we decided to take an evening stroll around the city. It's not far to Florence's main cathedral. The Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore is beautifully illuminated by floodlights. It's perfect and monumental.

It seemed to me that in Florence, most of the interesting places are concentrated in a relatively small area. You don't have to cover long distances. You can easily walk from one museum to another, from one beautiful square to another, and churches, cathedrals, bell towers, and other Catholic institutions are everywhere, each more beautiful than the next.

This is not surprising, since Florence was the cradle of the Renaissance. I have never seen such a large number of famous medieval artifacts in any European city.

We found ourselves on the Golden Bridge (Pointe Veccio)

This is a famous bridge where trade flourished even in the Middle Ages. It became "golden" when goldsmiths took a liking to it. Everything there is still so "expensive and opulent." At night, the boutiques are closed with special lids, like chests. These, oddly enough, are the most intriguing: a beautiful combination of wood carving, forged details, metal plaques, and patterned edging. We continue on to Piazzale Michelangelo. After wandering through narrow streets, we found ourselves at the top of the hill. There were quite a few people there, since it was a weekend. Many were sitting on the steps.

They're probably tourists like us, after all, Piazzale Michelangelo is one of Florence's most popular spots. The view of the city at night is mesmerizing. But it's impossible to stay here for long—we're literally smoked out. And it's time to go home. One last thing we need to see is the replica of the David statue in the piazza; a visit to the original is planned for the next few days. On the way back, we cross the Golden Bridge again. Now musicians are playing jazz. We stop briefly to listen and then head home. The restaurant across the street is already bustling with activity: despite the late hour, almost every table is occupied. But they found a spot for us. We wanted to have a quick dinner and then go rest, but they took a really long time to serve us. But we had the opportunity to get to know Tuscan cuisine better. Incidentally, we never really grew to like Tuscan bread; it's completely unsalted. This tradition arose long ago due to the high tax on salt. The unsalted bread was supposed to balance out the salty olives. The meaning of this balance eludes me. But the dessert idea was intriguing: sponge cakes with candied fruit and pistachios dipped in sweet wine. We're not big fans of sweet wines, but we'd agree to this dessert. It's also worth noting that Italians drink wine like compote, and not just sweet ones. Good wines are inexpensive in Italy. We'd often see friends or relatives enjoying a glass of wine at an outdoor restaurant in the evening. But we didn't encounter any overtly drunk people. I wouldn't call myself a wine connoisseur, but what we tried was quite pleasing in terms of price and flavor.

Living in the historic center of Florence has its advantages and disadvantages. The advantages are that everything interesting is close by, and the disadvantages are that everything interesting attracts crowds, which makes it incredibly noisy. But if you get up early and have a quick breakfast, you can escape the hustle and bustle for a while. However, street vendors are already setting up their stalls near the central market and laying out their wares. These are mainly leather goods. Florence is also famous for this.

I wish I could count the number of steps we had to climb and descend on this trip! Thousands! We head back to the cathedral, buy tickets, and climb the bell tower. The climb is not at all difficult after our walks in Cinque Terre. And we're incredibly lucky with the weather.

The city looks magnificent against the backdrop of the mountains in the morning haze. The cathedral's dome is very close. You could stand there for a long time and admire all this unearthly beauty, but we had to move on. Then we went to the museum in the People's Palace. Popolo palazzo) and to the Plaza de la Signoria (Senioria palazzo) .

Before lunch, take a stroll along the waterfront and stop at the market for groceries. Florence's central market, San Lorenzo, deserves special mention. It existed as far back as the Middle Ages. But the current building was built relatively recently, at the end of the 19th century. Inside, you'll find a fish market, a sausage market, stalls selling cheeses and olives, fruits and vegetables, Tuscan spices, sweets, and fifty varieties of pasta.

All this abundance makes your eyes dazzle and your mouth water, even if you're not hungry. And if you are hungry but lazy, the second floor is yours—a ton of cafes, restaurants, and eateries to suit every taste. But we're not lazy. We buy a cut of beef for a steak. The butcher is a professional. He asks how thick the piece should be. Italians are often easy to understand even without knowing the language, because they're good at explaining with gestures. The thickness of the steak is measured in fingers. The butcher points to three.» No, gracia,- We say when we're offered a generous cut of Florentine steak and opt for a more classic version, a finger and a half thick. And some fresh vegetables, herbs, cheese, and olives. I happily buy provisions because I realize I've missed cooking. After lunch, Denis "goes" to work, and I continue my stroll around the city.

I'm looking for Fort Basso on the map. It's very close. There's a park with a fountain next to it, and for some reason, there are a lot of Muslim families there. My next goal is to find the Boboli Gardens.

I found them, but a bit late, close to closing time, and decided to leave them for the next day. On the way back, I came across an ancient gate.

It wasn't entirely clear where the entrance and exit were. Later, I learned that the ancient fortress walls around the city had been torn down almost everywhere, as they were no longer needed. But gates remained in a few places. Not far from the gates, near the park, I saw a small village of cat houses. About twenty of them were sitting: some on the porch, some on stumps, some in the grass, some by their bowls. They were obviously waiting for whoever was feeding them. But I wasn't that person, and the cats lazily looked past me. And I was in a hurry to get home, because even though it was Italy, it was still October and it was getting chilly. .

Day Seventeen

How lovely – fresh buns from the bakery across the street for breakfast. In fact, buns were a daily part of our "Italian" life. I love Italian buns! Every bakery has something special and so delicious. It's a shame that we rarely have that in our everyday lives.

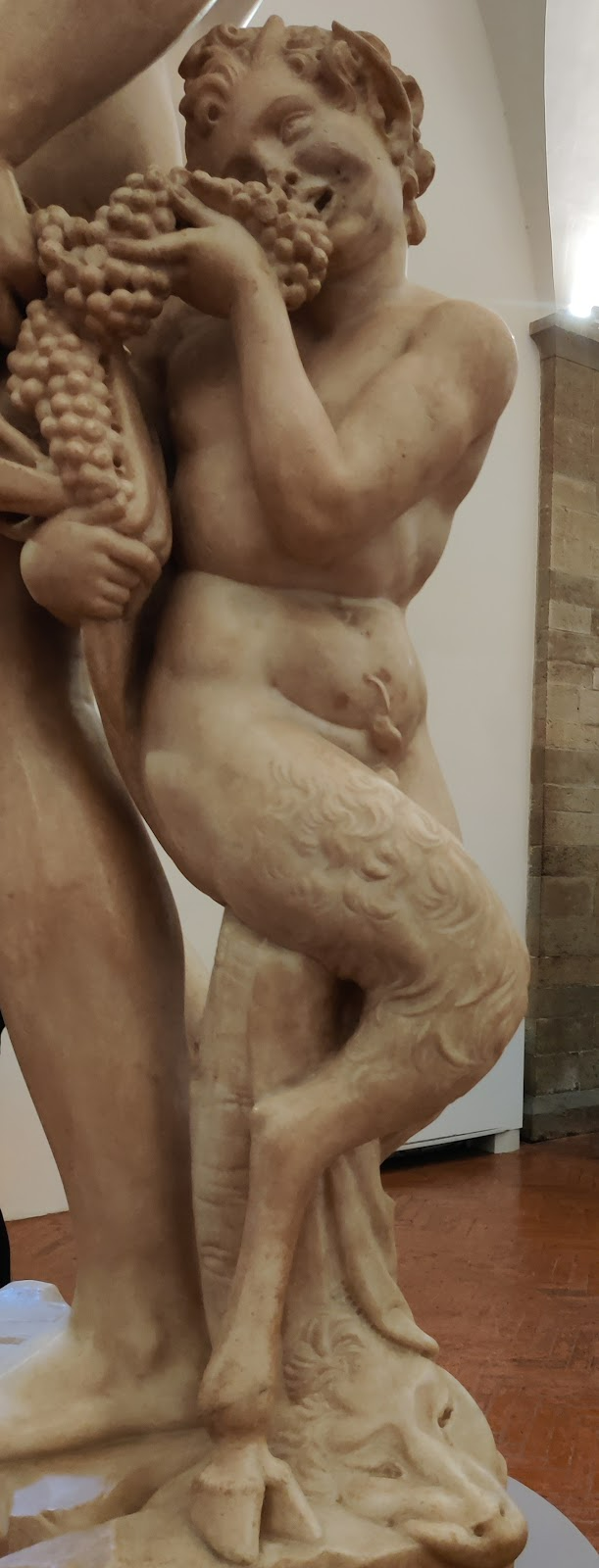

We quickly eat some rolls, drink some coffee, and then head out for a walk. Denis has a plan, but we didn't go far today, stopping at the Uffizi Gallery. Of course! I'd come to Florence and not visit the Uffizi Gallery! The museums here open early. It's a smart move to visit museums in the morning; there are far fewer people there. The Uffizi Gallery has a rich collection of exhibits. I remember as a child, I loved leafing through an album of Michelangelo's works. Even then, I was amazed at how stone could be made so beautifully. And now, suddenly, I saw everything that had previously only been on paper. I smiled at the familiar sculptures as if they were old friends. It must have looked silly from the outside.

The Roman Gallery evoked both surprise and admiration. How precisely and harmoniously the sculptors of those ancient times could convey the beauty of the human body! Specifically bodies, because the faces looked detached, without any emotion. Playing the game "say it with the word "Florentine," we first mentioned the Florentine school of painting, which was widely represented in the Uffizi Gallery: Donatello and Botticelli, Fra Angelico and Brunelleschi, Raphael and Caravaggio—it was simply dizzying!

Florentine syndrome—that's probably me and the Asian tourists who are obsessively photographing the masterpieces of the Florentine school. A few hours later, we emerged rather exhausted from all the art.

Now, to the Rose Garden! It descends in terraces from the mountainside, at the top of which stands the Church of St. Mark. The Rose Garden is for everyone, and that's what makes it so special. Autumn roses are few, but in summer, more vibrant colors are visible here. Here, among the roses, you can encounter a curled-up sleeping cat, a monument to a suitcase, and a dashing man in a coat and hat—all in the style of contemporary art.

The Boboli Gardens, however, were laid out for aristocrats: gravel paths, trimmed shrubs, fountains and sculptures, terraces and grottoes. However, over time, they evolved into something resembling a botanical garden.

They contain a wealth of interesting botanical finds. Denis and I are also a bit of a botanist at heart, so we wandered around there until we had to urgently return home. We ran out of time for the little Bobolki, as well as the Pitti Palace.

Day Eighteen

I find a list of 25 interesting places to see in Florence online. Today, the Basilica of San Lorenzo and the art gallery are on the list. At the gallery, I run into another old friend.

Here he is, a handsome man!

As I write this blog, there's a furor online about a school (I think it's in Florida) where a teacher showed sixth-graders a statue of David, and parents declared it pornographic. The teacher was ultimately fired. "You should have warned them when you show something like that!" the parents protested.

Ignorant people! David is perfect!

Denis is tired of museums, feeling gloomy and jaded by art. He's not prone to Florence syndrome. As I mentioned earlier, the historic part of Florence isn't very large, and famous museums and architectural landmarks are located close to one another. Another problem is that you don't have time to rest. Your head is swollen, and your brain refuses to process the enormous amount of visual information. Or maybe you need to plan your visits more wisely. Three museums in a row is probably a bit much, but you want to see as much as possible!

I send Denis to work, and I

I go for a wander through the surrounding hills. At the top of one of them is a beautiful castle. I find it on the map and decide to walk there.

I wander for a long time among stone walls and narrow streets. Suddenly, I come across Tchaikovsky's villa. The great composer could afford it! The muse probably visits more often in beautiful places. But the castle I was aiming for turned out to be private property and off-limits.

In the evenings, when my legs are already falling off from walking, I put on headphones so as not to disturb a working family member, and selflessly watch a multi-part documentary about the Medici dynasty, which had a great influence on medieval Florence.

Day nineteen

That day, I ask Denis to choose where else to go. "Just not to the museum!" my husband declares. And I reluctantly agree, thinking: "Why did you stop in Florence for a whole week?"»

We decided to take a stroll through the hills around the city, and at the same time find an archaeological dig site at an Etruscan settlement. First, we walk for a long time through dark tunnels covered in graffiti, past railroad tracks and walls also covered in graffiti. Denis suggests viewing all this art as contemporary art. Incidentally, there are some pretty good ones. But the best graffiti, of course, is in Portugal and Mexico.

Finally, the urban landscape gives way to rural areas: vineyards and olive groves.

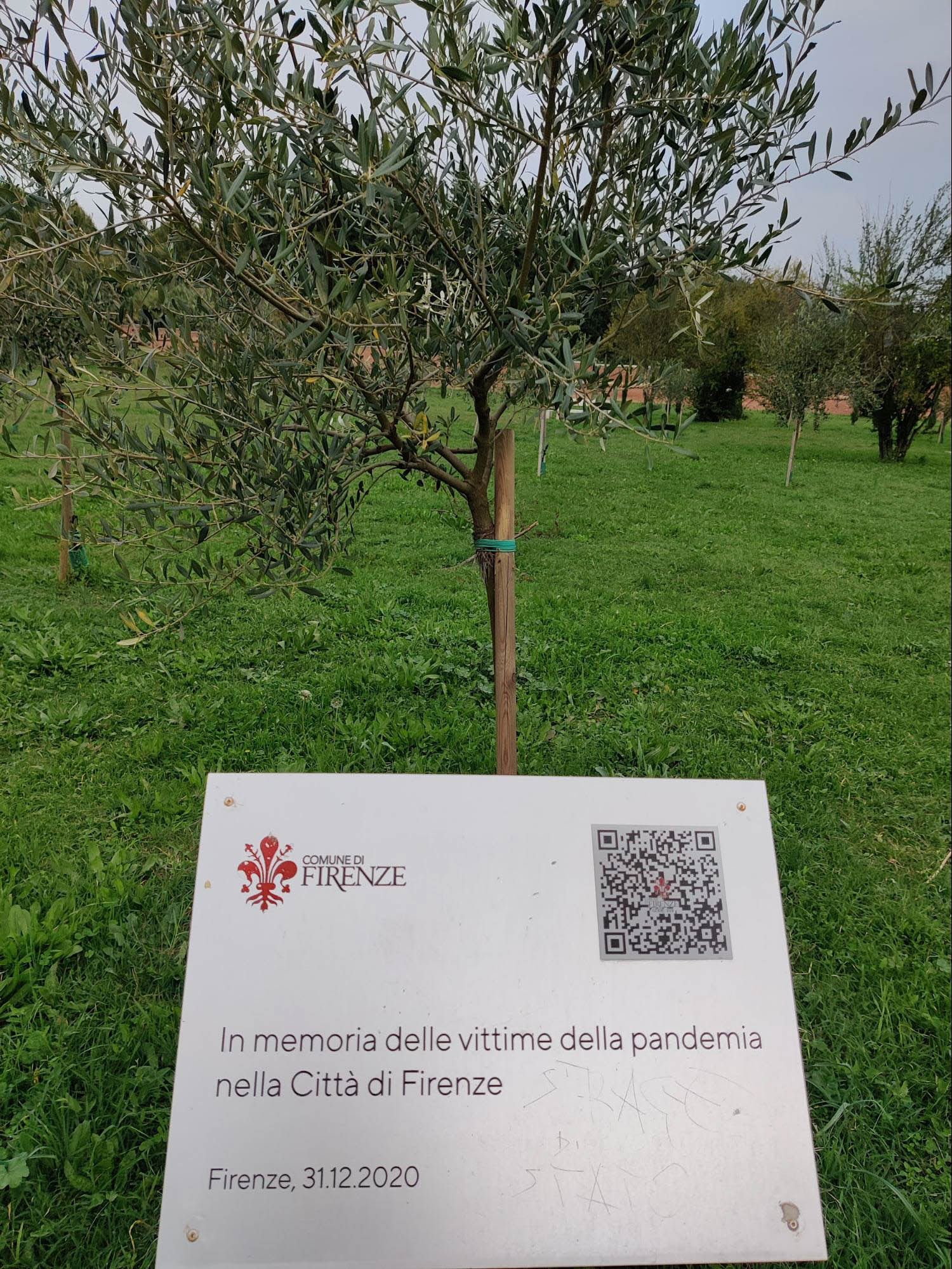

A little further uphill, and we emerge into nature. A beautiful view of the valley opens up from the hill. We spend some time contemplating the views and indulging in various meditations. Then, a rocky road leads us to a young park established in memory of COVID-19 victims.

There are so many victims that it becomes a long alley. It becomes sad.

After the traditional cup of coffee, Denis still had a little time left when he suggested we visit the weapons museum, which was based on a private collection. I didn't mind. This was also a concession to Denis. Fortunately, the museum turned out to be small, and the weapons collection was interesting.

While Denis is already working, I manage to run to the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore to admire Michelangelo's frescoed vaults. From the inside, the domes look like celestial spheres. The scale is astounding. The illustrations in that childhood album couldn't convey the scale and depth of the frescoes. I stare at the familiar scenes for a long time until my neck starts to ache. Below, in the crypt, you can see the foundations of an earlier church, on the site of which the cathedral was built. It's also the burial place of the brilliant architect Brunelleschi. I learned about him from the same film I watched several evenings in a row.

That was it. It was our last evening in beautiful Florence. A little later, we took one last stroll through the city's ancient streets. We said goodbye to the boar and the frog. We strolled along the river once more and took a last look at the Piazza della Signoria.

Tomorrow we leave for Rome. .